The Power of Self-Organization

The Power of Self-Organization

Florian Wüst: In 2016, you published a book entitled SAVE, a very impressive book, in my view. No pictures, no white space, text from start to end. Even the cover isn’t a cover in the real sense of the word, but the first page of the book. “I want to get out of here, but I don’t know where to or what I would want there.” Beginning with this sentence, you move on to the French Revolution, in the middle there’s a brief paragraph on a childhood memory. This sets the tone for the whole book, a montage of personal and political stories—although I don’t mean to say that they are separable from one another—an encyclopedia of encounters, most of them with people working for social change. Confusion as a point of departure for dealing with matters of great urgency. What gave the inspiration, what motivated you to undertake such a project? Did you write and publish prior to this?

Jennifer Bennett: The idea of starting the text right on the cover came from the graphic designer Christoph Steinegger, who really understood my approach. I’ve written ever since learning to write. It became a possibility for me to formulate thoughts and feelings without necessarily having to share this “speaking” with someone else. Writing opened a private space for me and my thoughts. I published my texts for the first time in 2000, after a trip to the U.S. Working on a book like SAVE was inspired by a constant sense of feeling alienated and estranged from a lifestyle and a consumer culture that hardly had anything to do with how I want to spend my life with other people. Another important aspect was that I felt I was an accomplice of situations that I reject: paternalism, nation-states, exclusion, waste, pollution, exploitation, oppression, etc. I knew I wasn’t the only one, that this aversion was shared by many, and I wanted to collect voices that speak about real problems, that tell of other possibilities of organization, of joint living, of values and collaboration. I wanted to combine all these forces in the real world and initiate a collaboration that would lead to the overcoming of what I reject. I imagined a kind of transnational alliance that would replace our current structure, organized around nation-states and representation. I place great stock in the power of self-organization, which is always at work, even under current conditions.

Florian Wüst: The living moment of “speaking,” speaking with one another, searching for the right words, setting thoughts in the flow of speech: all of that is kept in SAVE, not edited out. I read this as a gesture or better a stance, on the one hand, not subverting the plurality of the voices by smoothing out the language, at the same time emphasizing the role of subjectivity and locality, precisely when it is about opposition against hegemonic orders.

Jennifer Bennett: Various things come together here. First of all, I held the conversations in the language of those being interviewed. In Spanish, that means that I translated the language only when transcribing, and sometimes I only really understood what had been said while writing it down. I didn’t want to make this hesitant comprehension disappear with a professional translation. The languages in which the conversations were held is noticeable in the text, in the case of the English conversations, entire passages were left in English, since a language already contains an explicitly unique mode of expression, in principle its very own way of thinking. In addition, I was interested in making legible the fact that these conversations emerge because two people encounter one another and that this encounter triggers a specific form of speaking. I like keeping in mind that I only come up with some ideas because of a specific conversational partner, that communication is something that is always unique.

Cristóbal Moro, law student, Santiago de Chile

Jen: Here’s a different question, are there Mapuche students at the university?

Cristóbal: There’s one, he is the most relaxed of all us. That also can cause problems, he’s always late, that’s just the way he ticks, our boss gets furious. It’s just a different way of working.

Jen: He doesn’t have our pressure.

Cristóbal: I’d like that. It’s a philosophical principle, and I think this discourse is really important. Our Western system is self-destructive. The discourse of the “good life” would do us a lot of good. Because it implies a reduction in thinking about progress. It implies taking account of things that are totally natural and human. A relation to the earth, to identity. It is a conception that is essential. Reducing consumption. There is, despite everything, even if it’s not talked about, a kind of magic consciousness. Like a kernel of imaginismo mágico. But all the same, there is a really Calvinistic relationship of work, we always need to be doing something. Santiago is a hysterical city, everything is always in motion.We spoke about TTIP agreement and fracking.

Jen: It’s like the U.S. has become a wild animal and that the strongest partner is still the EU, I see that as a problem.

Cristóbal: I think the next big thing that’s going to happen will take place in South America. But I think Chile is lost. There are so few here that have such unbelievable amounts of power and means at their disposal. A few families, and the people know who they are. For example, before the metro and the busses, there was a different system, it was chaotic but it worked. Then Michelle Bachelet did a copy and paste of the European system and it doesn’t work, the reality here is just different. And instead of destroying the system, you see endless lines of people waiting in silence. When that happens in Argentina, the bus doesn’t come, they just destroy the whole thing. That’s why I think the trauma of the dictatorship, because it was so brutal, made the people docile. If I were a dictator, I would come to Chile. The thing is, Pinochet is dead and the people celebrated on the streets because he was dead, but he was never tried before a court of law. And that means he died with the legitimacy of his dictatorship still intact.

Jen: Do you think that could repeat itself?

Cristóbal: Not in the international context, that would be difficult. But there are just a few families that own this country and they are afraid—and they have every reason to be. But the level of police brutality is still quite high. In Argentina they also had a dictatorship, but the perpetrators were tried and convicted, that’s a big difference. Ours just died.

Jen: I’ve been to the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos and one of the eyewitnesses said that the worst thing was that the country was divided.

Cristóbal: And it still is. When there is social unrest on the streets, there are people who say it’s time to get the military back on the streets. There’s a normalization of violence.

Florian Wüst: In your observations and conversations, you disperse background information on certain terms, historical events, and people, made visible with a different writing. One could say that SAVE is a hyperlinked text in book form. Did you plan that from the very beginning? Have you thought of realizing the whole thing as an internet blog? And to combine it continuously with direct links to the many online sources that you used for the book?

Jennifer Bennett: At the start, I envisioned a kind of serial novel, like the pulp novels you can buy at the newspaper stand. When my partner left me in this process, I took a break for three years. Then I travelled to Argentina to visit an old friend. I took my notes with me and planned the structure of the book. I inserted research fragments because while working on my old notes I noticed how much historical events, various projects and individuals influenced my life because they shaped the course of history. Documenting history in books, that makes sense to the extent that books are something long lived. I found it fascinating how the Internet shapes our current production of knowledge. Many of the research inserts are from Wikipedia, some of it horribly written and abridged. All the same, I’ve learned a great deal, and I wanted to direct attention to what it does to our thinking and understanding when it is always interrupted by a listing of facts. An acquaintance of mine called the book “post-Internet literature.” In addition, while travelling I kept a blog in which I included links to the locations and organizations. I’m currently thinking about putting the book online, expanding it with links and to allow others to contribute as well, to create a platform for networking. But that will take time.

Denis Rochac, Earthworks, Boggs School, Detroit

Jen: As we see, leaders are still important.

Denis: Yes, but I’m not really a fan of that.

Jen: I think we’re brought up to need leaders.

Denis: There’s no flow of leadership and the history is that way: Rosa Parks decided to sit down where she did, but there was a great deal of action and workshops and things before that, she wasn’t alone. That’s the reason we always believe in the leader, like Martin Luther King, but they all could be diminished, but the capitalist system always wants a logo that can be sold. They give you a Che Guevara t-shirt and let you think you’re part of something, and of course we all want to be part of something, don’t get me wrong. But I think we should do as much as possible without funding and in the end we won’t have any jobs, but we’ll have other things out of which things can develop.

Florian Wüst: I like that the title is SAVE, as opposed to safe. Save something, like money. Securing something or saving it: our own lives, the planet. Preserving something. All of this describes active involvement.

Jennifer Bennett: It was quite a challenge for me to think up a title. Since I wrote so much and used the save function so often, the concept forced itself a bit upon me. But “save” means just what you say. For me, it was about saving perspectives that are marginalized and are not made part of the mainstream of history. At least not yet. It would be something I’d like to pursue, promoting an awareness of different kinds of commoning, for example.

Florian Wüst: Good that you mention that. There’s been a lot of talk about commoning, especially in the urban discourse. But it seems to me that the prerequisites for creating and preserving common spaces that aren’t only shared, as Stavros Stavrides writes, but themselves play a role in defining sharing are quite different from one another. I don’t think that it would be any easier here, say, in Berlin, where there is a state infrastructure that works comparably well, albeit in a very formalized fashion. On the contrary. In relation to your encounters with various, especially indigenous initiatives between Temuco in southern Chile and Detroit: How does the power of self-organization manifest itself? Can locally developed methods be transferred and abstracted?

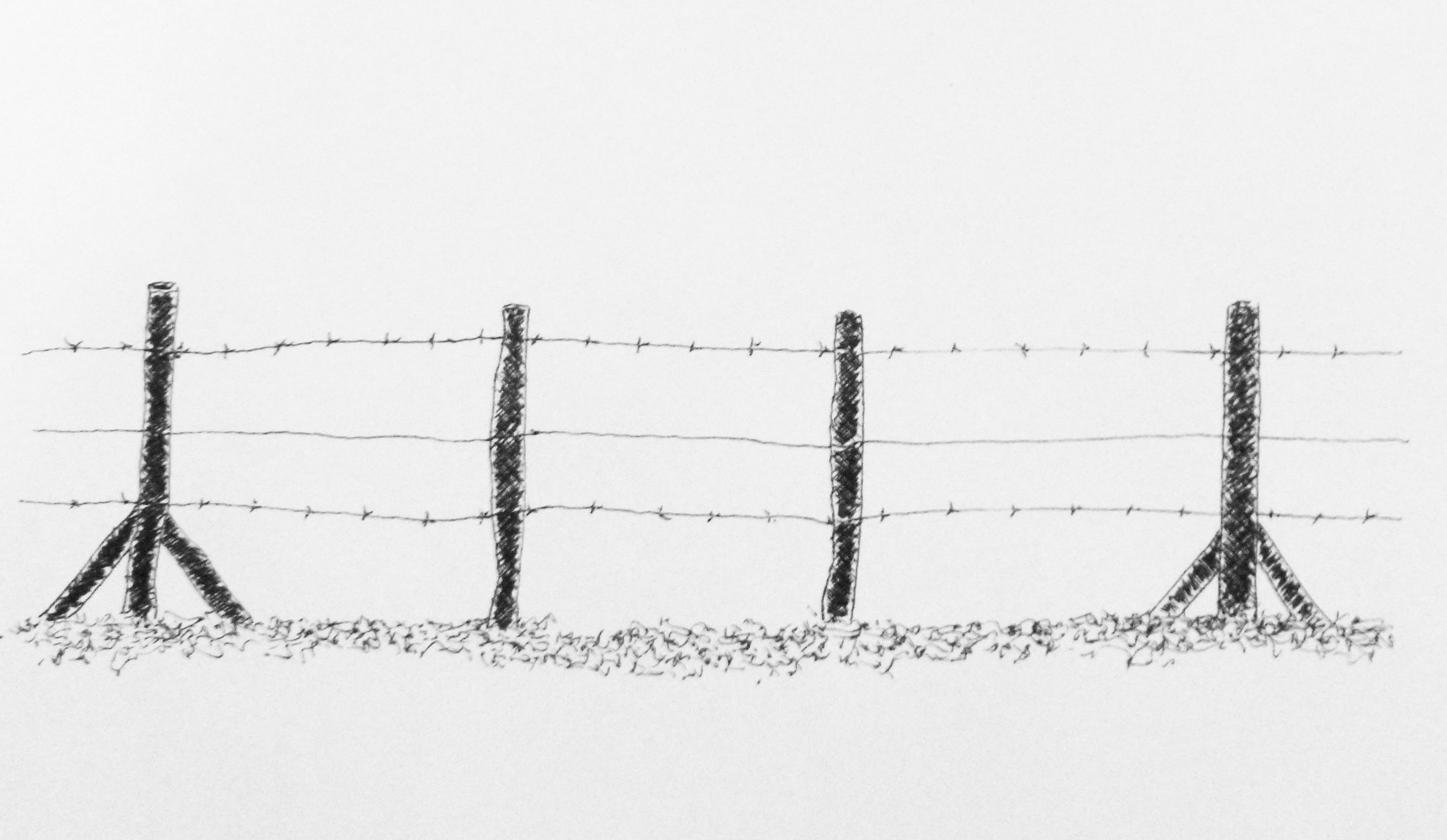

Jennifer Bennett: Precious stones are a good example of something that can only form in certain locations. Even if we are growing together to form a global community, something that is desirable in light of the problems we are confronted with, I think it would be a loss to want to level out regional differences. So yes and no. We can learn from others, but copy and paste often doesn’t work in reality. Fundamentally, I think that self-organization has to do with collective practice. The power of self-organization means that people work together towards solutions that allow them to emancipate themselves and to thus have new experiences. A group of Mapuche in Chile is occupying territory that they consider rightly theirs. In European cities, we are only gradually coming back to the idea that something could be rightly ours, beside our labor power. This self-conception is not very well developed among us. To occupy something, we have to organize, that is the power of self-organization. As I see it, the instrumentalization of self-organization via participative techniques merely for the sake of appearances is a problem. As I found out in conversations with members of the various indigenous groups that need to be included in planning infrastructure projects according to Treaty 169 of the International Labor Organization of the United Nations, the key decisions had already been made in the run up. This kind of so-called citizen participation seem like a waste of time and energy without being able to decide on important points or to reject an entire project.

Kyle, Member Dancing Rabbit Eco Village, Alternative building enthusiast

Kyle: I want to say something about what you said at the start, how people are complicit with a system that they didn’t understand and didn’t want to support. I thought about forms of control and what about the concept of hegemony, that is, controlling people through positive converts essentially, and I have the feeling it’s a major component of our contemporary system and how it runs and everyone’s just part of it and not really paying attention to what’s going on, that’s all made possible by the quite affordable energy resources that we have, through fossil fuels. I think the fact that we have a lot of oil, coal, petroleum, these resources enable in an artificial way a system where people can achieve comfort and achieve material happiness, but this system is not going to sustain itself. When these possibilities disappear, people will be to acknowledge these systems in an uneasy way. That’s why something like Dancing Rabbit is very important to me, because I have the feeling we have a concept of conserving resources. We are quite conservative when it comes to living, not politically, but in what we consume and how we deal with space. We figuring out how to live in a such a society. The whole Marx idea that the resources determine the superstructure. That’s why I think dealing with resources realistically is a fundamental part of redefining nation states or society or ecovillages or whatever.

Florian Wüst: In the Uneasy Alliances Study Circle at the transmediale 2019, you posed the question: “How to disrupt the status quo?” I assume you weren’t primarily concerned with the status quo everyday political life, in which progressive approaches from below are appropriated and neutralized, as happens all too often in participatory processes. The subject of the Study Circle revolved around the challenge of conceiving new kinds of alliances and practicing them, beyond those what is familiar, close by, what’s easy. How would you answer the question?

Jennifer Bennett: I would tend to say: the status quo of oppression. We could destabilize it by actually entering into different kinds of relationships. Relationships of parity to everything that surrounds us, recognizing that everything around us has the same right to existence as we do. That’s difficult, I notice it in situations where I want to convince someone of my own views. For me it’s not about negating arguments, it’s nice to be part of a movement of communication and to slowly come away from my own convictions because I’m ready to learn from someone else. At the same time, it’s about accepting differences, achieving possibilities that different ideas can enter into an exchange and that a mutual movement is made possible. Rosi Braidotti writes about this in her very readable little book entitled Per Una Politica Affermativa: “Together we will become something different than we were before we became close to one another.”

Florian Wüst: At the end of your book, you return to Hamburg where you conduct the last interview with Andreas Blechschmidt from the squatter’s initiative Rote Flora. You speak to him about the difficulty of leaving one’s own peer group, of sensitizing others that they have more in common with the political world of the squatters than they think, like the problem of rising rents. That is, the difficulty of entering into a movement of communication like you have just named it. Where do you see yourself today, living in Berlin, quite concretely in your practice and in comparison to four to nine years ago, when you were working on SAVE? The book not only begins with an open question, but closes also in a similar way under the impression of an urgent and unsolved here and now. “It drives me up the wall. I have to find something out. I have to do something. That I and we cannot live if it doesn’t stop, the way the world is upside down. It’s upside down, it doesn’t work. It only works for a few.” For some time now you have been active with Kunstblock and beyond, an alliance of artists that primarily focuses on the subject of gentrification in Berlin and fights against it.

Jennifer Bennett: I think it’s necessary to be active as an artist and for that Kunstblock is a good form of organizing. Anyone who wants to can participate. We meet once a month and also meet in work groups, we often write joint texts for which we use online pads. It’s irrelevant who did what, we meet for joint actions. For example, to support protests of the homeless or to uncover artwashing strategies and to make them public. We are a small group, although there are loads of things we could concern ourselves with. Once you get started with hotspots of spatial policy, they pop up all over. Although the so-called BerlinStrategie, the city government’s urban development concept for 2030, writes about Berlin being a diverse city of solidarity, there’s not much sign of it, in a reality where construction permits for high price co-working spaces are granted, where private property is promoted and there’s a focus on touristification. I don’t understand why we even have to struggle for environmental protection and the common good, but capitalist reality shows that it’s necessary. If it weren’t necessary there would be no homelessness or insect death. It is as if I have had to watch how everything that can be done wrong is done wrong. Sometimes, it’s almost unbearable and generates aggression and frustration. I admit these feelings, even though I’ve often been accused of being negative. But I really want it to be understood that the sentence at the end of the book, “It’s upside down, it doesn’t work. It only works for a few,” is real and that we can’t simply ignore it. In our conversation for SAVE, the philosopher Frithjof Bergmann says there are 20 percent oasis people and 80 percent desert people. An order where a relationship like this is considered balanced is something I find very problematic. I think it’s necessary, as I said at the beginning, to replace this order. In my view, this requires an overcoming of being governed by representative political parties. Politics should not be a competition and not a struggle between left and right and above and below. Current problems affect us all and we should ensure that an awareness of the problem is created, strengthening connections and not promoting animosity. Ralph Heidenreich said something inspiring regarding the French Revolution. He said that it was only possible because in the realm of “administration” everything had been prepared to replace the ruling feudal class. To replace an old structure, a new one has to be developed and establish itself. Art can offer a possibility of creating test areas and to reflect on such issues in the framework of collective work and participatory projects. For me personally, it helps not just to work alone as an artist, but in a collective to practice collaboration and to open myself to different approaches.

Andrea Stander, Executive Director of Rural Vermont

Jen: Can you start by telling me how Rural Vermont got started?

Andrea: Sure. It started in 1985, because there was a crisis among the farmers in Vermont at the time. It was a group of people who were farmers and people who cared about farmers that got together to find out what could be done to have our voices heard and that they could have an influence on the laws that were made that influenced them and the possibilities they had to earn a living on their land. The mission of the organization continues to be about enabling people who work the land to come together to promote their shared interests and to find a way to bring their concerns to the addresses where change can happen, be it on the local level in their communities or in the state or on the national level, although I would say that we mainly deal with things from our area. In Vermont.

Jen: That makes sense in terms of regional interests.

Andrea: Yes, and we were always small and grassroots focused, to the extent that we always took our directions from our membership and our board, most were themselves working farmers. We don’t have many employees and rely on the volunteering of our membership. For almost thirty years, many problems have remained the same, for example, economic fairness is still an important aspect. Especially the small businesses that are mainly family farms have to play on the same level as the large agricultural companies, that’s a problem.

Jen: Do you know why large companies receive subsidies? That makes no sense.

Andrea: No, nothing makes sense in this discussion. I tell people all the time that if you go into this area, leave logic at the door, it makes no sense. It’s a political system that has been developing since the 1970s. I don’t know if anyone’s mentioned the name Earl Butts, he was Secretary of Agriculture in the 1970s. He said to the farmers in the. Mid-West, “Get big or get out.” And that marked the start of the transformation of agriculture. It was a political decision that it was more important to produce cheap food than good food. Many political decisions were made along those lines and the corporations grew. At the time, the politicians thought that if the food prices rose too dramatically, and that’s the way it seemed at the time, there would be a revolution in this country, that was one way of stabilizing the situation. They kept prices artificially low. But in recent years, the prices still rose massively, for various reasons.

Jen: Who controls the prices, the price of milk, for example?

Andrea: If you participate in the global market, you have no influence on it. If you sell things on the Farmers Market, it’s much more local. There are huge price differences in the various regions here. That has to do with the population and the prices they can pay. But it makes no sense that something so important as the food produced is controlled by large companies who have no interest in nutritious food.

Jen: What choice do the people have? Especially the poor people, they really have no other choice. And I think it’s thought, until now nobody has been hurt, or we don’t know how damaging gene-modified food can be.

Andrea: Yes, that’s another problem, the revolving door between the regulators and the companies. Some people working as policy makers in the agricultural sector once worked for Monsanto. And these interests have influenced so many decisions over the past thirty years. And some really think that these technological solutions would work and really believe it’s not damaging. I think there’s sufficient doubt, insecurity, and enough disturbing evidence.

Jen: Since when have there been GMOs in the United States?

Andrea: The first were introduced into the human food chain in the 1990s.

Jen: They’ve been planted since the 1990s?

Andrea: Yes, and before that they were used for animals. It’s only recently that GMOs have been produced for direct human consumption. Most of them are consumed indirectly, because it is fed to livestock. Or as ingredients in processed foods. But it’s always said, “That’s such a small amount, that doesn’t matter.” But what in my eyes is the most convincing: I’ve seen two charts that apparently have nothing to do with one another. One is a chart showing the increase in genetically modified foods, and the other shows the increase in illnesses of the digestive system, and they look exactly the same for the time period in question. Of course, other factors are involved here, that we don’t take the time to eat, always eating on the go and the like. But our ignorance regarding genetic technology is huge, we know very little. It’s a trial-and-error process, which is primarily driven by what we want as people, “Oh, we like this better than that, let’s make a lot of this.” And now these decisions are being made by multinational companies whose sole interest is making more money. And not seeing us as part of the world, separating ourselves so much from it, is perhaps our greatest mistake.

Translated from the German version by Brian Currid.