Selling the Future at the MIT Media Lab

Selling the Future at the MIT Media Lab

What follows are some of my initial findings as I’ve been researching the past and present of the MIT Media Lab, a lab founded in 1985 by former MIT President Jerome Wiesner and Nicholas Negroponte of OLPC fame, which was then directed by Negroponte for the first twenty years of its existence. The MIT Media Lab has become synonymous with “inventing the future,” partly because of a dogged thirty-year marketing campaign whose success we can measure by the fact that almost any discussion of “the future” of technology is a discussion about some project at the Media Lab.

Of course the lab has also become synonymous with the notion of inventing the future because of the central role it has historically played in the fields of wireless networks, field sensing, web browsers, and the Web, as well as the central role the lab is currently playing in neurobiology, biologically inspired fabrication, socially adaptive robots, emotive computing—the list goes on and on. You would be right to think that the lab has long been driven by an insatiable thirst for profit, operating under the guise of an innocent desire to perform computerized feats of near impossibility, decade after decade.

I’ve also come to see this performance as partly a product of a post-Sputnik Cold War race to outdo the Soviets no matter what the project or the cost. In Stewart Brand’s 1986 The Media Lab, the only book written so far exclusively on the MIT Media Lab, he writes with an astuteness I don’t usually associate with him:

If you wanted to push world-scale technology at a fever pace, what would you need to set it in motion and maintain it indefinitely? Not a hot war, because of the industrial destruction and the possibility of an outcome. You’d prefer a cold war, ideally between two empires that had won a hot war. You wouldn’t mind if one were fabulously paranoid from being traumatized by the most massive surprise attack in history (as the USSR was by Hitler’s Barbarossa) or if the other was fabulously wealthy, accelerated by the war but undamaged by it (as the US was by victory in Europe and the Pacific). Set them an ocean apart. Stand back and marvel.

Brand then goes on to explain how much American computer science owes to the Soviet space program—resulting in the creation of Eisenhower’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, which by the 1970s had an annual budget of $238 million and funded many labs at MIT. And even when ARPA changed to DARPA, to show that all agency projects had direct defense applicability, the organization continued to fund labs such as the predecessor to the Media Lab, Nicholas Negroponte’s Architecture Machine Group. Still to this day, even though the Media Lab is famous for its corporate sponsorship, the US Army is listed as one of its sponsors, and many of the lab’s projects still do have direct applicability in a defense context.

But the lab is also the product of MIT’s long history of pushing the boundaries of acceptability in higher education in terms of its deep ties with the military industrial complex and corporate sponsorship that goes back even to the 1920s. However, we now know that even though MIT tried to work with corporate partners in the post-World-War-I years as it tried to pay for research programs in chemical and electrical engineering, the depression put an end to corporate partnerships until late in World War II. World War II in fact became a decisive turning point in the history of university science and tech labs, likely because of the enormous amount of funds that were suddenly available to sponsor research and development contracts.

Historian Stuart Leslie reports that during the war years MIT alone received $117 million in R&D contracts. So again, once the “hot war” was over in 1945, it was almost as if MIT needed a Cold War as much as the state did, so that it would continue to receive hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of contracts. By the 1960s, physicist Alan Weinberg famously said that it was getting increasingly hard “to tell whether MIT is a university with many government research laboratories appended to it or a cluster of government research laboratories with a very good educational institution attached to it.”

Also in the 1960s, the Research Lab of Electronics (or RLE) division was getting the lion’s share of the funding. RLE was a lab created in 1946 as a continuation of the World-War-11-era Radiation Lab, which was responsible for designing almost half of the radar technology deployed during the war. The RLE also became the template for many MIT labs that followed— particularly the Architecture Machine Group. RLE was one of the first labs to be thoroughly interdisciplinary, to train grad students who went on to write the books that future grad students read (and then responded to by writing other books or going on to fund tech companies), and it also groomed future leaders either of the lab itself, the university as a whole, or for government or industry. Given this beautifully efficient system of using labs to both create and replicate knowledge, it makes perfect sense that researchers Vannevar Bush and Norbert Weiner—famous in part for their roles in advancing war-time technology—were also MIT teachers of Julius Stratton, the founding Director of RLE, and Jerome Wiesner, before he co-founded the Media Lab.

Wiesner’s life in corporate- and government-sponsored labs began in 1940 as he was appointed chief engineer for the Acoustical and Record Laboratory of the Library of Congress. His job at the time mostly involved traveling around the south and southwest, funded by a Carnegie Corporation grant, with folklorist Alan Lomax, to record local folk music. Two years later Wiesner joined the RadLab at MIT and soon moved to the lab’s advisory committee; during his time there he was largely responsible for Project Cadillac, which worked on the predecessor to the airborne early warning and control system. After World War II, the RadLab was dismantled in 1946 and in its place the RLE was created, with Wiesner as the assistant and then associate director and then director from 1947 to 1961. Weisner then served Kennedy as chair the President’s Science Advisory Committee from 1961 until the president’s death in 1963, and then served President Johnson for another year. He mainly advised the presidents on the space race and on nuclear disarmament. In 1966 Wiesner moved back to MIT as university provost and then as president from 1971-80. With Nicholas Negroponte at his side, he started fundraising for the lab in 1977 while he was president and became co-founder of the lab in 1985, once he had stepped down as president and returned to life as a professor.

This is my brief history of one side of the Media Lab’s lineage that extends quite far back into the development of the military-industrial complex, and especially the years of the Cold War, by way of Jerome Wiesner. Now I will move on to discuss the corporate, anti-intellectual lineage operating under the guise of “humanism” meshed with futurism, through the figure of Nicholas Negroponte. The son of a Greek shipping magnate, Negroponte was educated in a series of private schools in New York, Switzerland, and Connecticut, and he completed his education with a MA in Architecture at MIT in the 1960s. Interestingly, his older brother John Negroponte was a deputy secretary of state and the first ever Director of National Intelligence. In 1966, the year Wiesner returned to MIT to become provost, Nicholas became a faculty member there and a year later founded the Architecture Machine Group, which took a systems theory approach to studying the relationship between humans and machines. While the Media Lab’s lineage on Wiesner’s side runs through the Research Lab in Electronics and, earlier, the Radiation Lab, on Negroponte’s side the lineage runs through the Architecture Machine Group—a lab that combined the notion of a government-sponsored lab with a 1960s-70s-appropriate espoused dedication to humanism meshed with futurism.

But especially as this particular brand of humanism has always been tied to an imaginary future, it was a particular kind of inhuman humanism that began in the Architecture Machine Group and went on to flourish in the Media Lab. This philosoophy constantly invokes an imagined future human who never really comes into existence, partly because the future is ever-receding, but also because this imagined future human is only ever a privileged, highly individualized, boundary-policing, disembodied, white, western, male human. I think you can see the essence of the Negroponte side of the Media Lab in three projects I want to touch on. The first, from the early years of the Architecture Machine group, was unglamorously called the “Hessdorfer Experiment,” and is glowingly described by Negroponte in a section titled “Humanism Through Intelligent Machines” in The Architecture Machine, a book written in 1969 and published in 1970.

In the opening pages of the book, Negroponte mostly lays out the need for “humanistic” machines that respond to users’ environments, analyze user behavior, and even anticipate possible future problems and solutions—what he calls a machine that does not so much “problem solve” as it “problem worries.” His example of what such an adaptive, responsive machine could look like is drawn from an experiment that undergraduate Richard Hessdorfer undertook in the lab the year the book was written. Writes Negroponte, “Richard Hessdorfer is...constructing a machine conversationalist... The machine tries to build a model of the user’s English and through this model build another model, one of his needs and desires. It is a consumer item...that might someday be able to talk to citizens via touch-tone picture phone, or interactive cable television.”

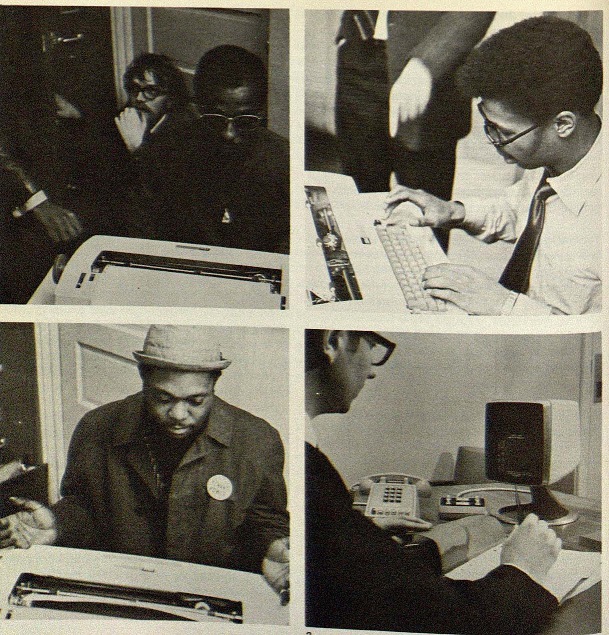

To help him build this machine conversationalist, Hessdorfer thought it would be useful to bring teletype devices into a neighborhood in the south side of Boston, what Negroponte calls “Boston’s ghetto area.” Negroponte writes:

Three inhabitants of the neighborhood were asked to converse with this machine about their local environment. Though the conversation was hampered by the necessity of typing English sentences, the chat was smooth enough to reveal two important results. First, the three residents had no qualms or suspicions about talking with a machine in English, about personal desires; they did not type uncalled-for remarks; instead, they immediately entered a discourse about slum landlords, highways, schools, and the like. Second, the three user-inhabitants said things to this machine they would probably not have said to another human, particularly a white planner or politician: to them the machine was not black, was not white, and surely had no prejudices.

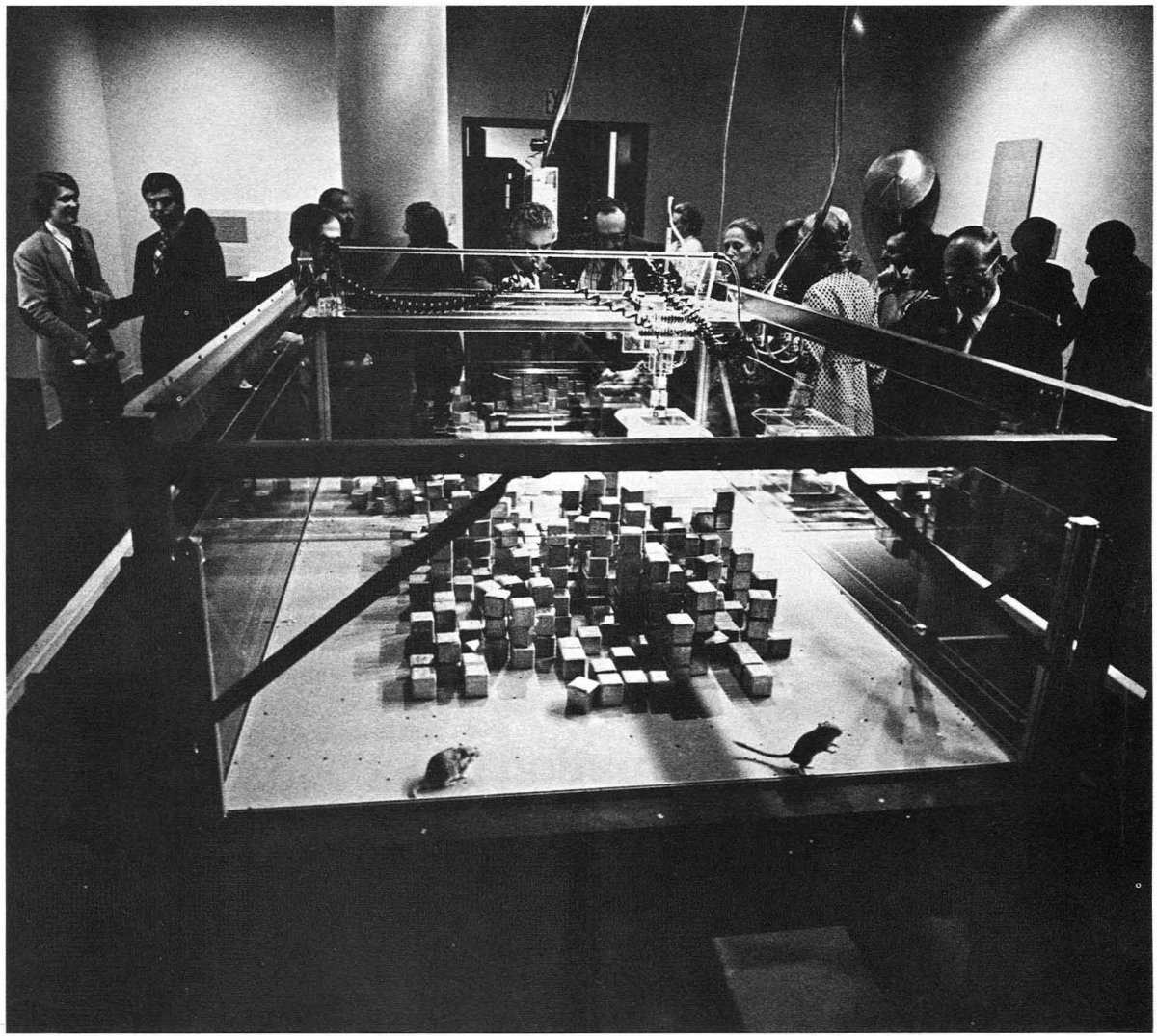

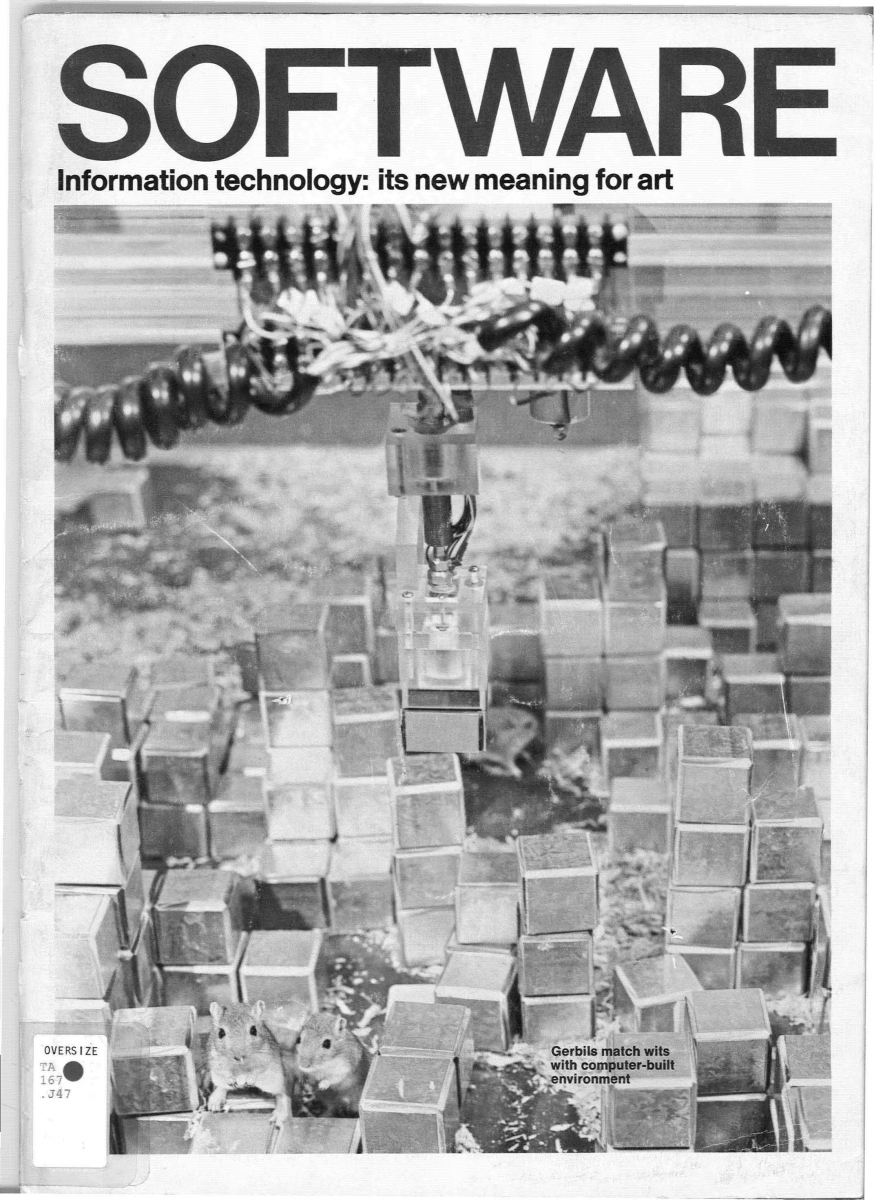

I barely know where to begin with this passage except to say that the entire racist, deceptive undertaking is, for me, about as far away from a humanism that acknowledges the lives of these particular humans as you can get. It also clearly demonstrates what can happen when we believe so completely in the neutrality of the machine—or its assumed capacity to give us pure, unmediated access to reality—as to think it can be called on as a magical mechanical solution to any human problem. Got a race problem? Get a computer! The second project from about a year later, also run through the Architecture Machine Group, is just as disturbing. This time the subjects in the experiment are not African Americans but gerbils. The experiment, called SEEK, was exhibited as part of a 1970 exhibition at the New York Jewish Museum called SOFTWARE. It consisted of a computer-controlled environment contained by Plexiglass, which was full of small blocks and gerbils. The gerbils were there to change the position of the blocks. A robotic arm was then supposed to analyze the gerbils’ actions and try to successfully complete the rearrangement according to what the machine thought the gerbils were trying to do. Unfortunately, the experiment was a disaster. As Orit Halpern puts it, “The exhibition’s computers rarely functioned...the museum almost went bankrupt; and in what might be seen as an omen, the experiment’s gerbils confused the computer, wrought havoc on the blocks, turned on each other in aggression, and wound up sick. No one thought to ask, or could ask, whether gerbils wish to live in a block built micro-world.” Again, this brand of humanism in the name of the future is one that has very little to do with situated-ness (or what’s now called posthumanism)—instead it has everything to do with abstraction and transcendence in the name of producing consumer products or R&D for the military-industrial complex.

The last example I’d like to touch on is the One Laptop Per Child Project, which Negroponte took up as an explicitly Media Lab project in the early 2000s and which, again, continues these same themes of humanism meshed with futurism combined with an espoused belief in the neutrality of the machine. The difference now is that even the guise of academic rigor and a scientific care for method seen in the Architecture Machine Group has transformed, probably because of the lab’s responsibility toward its 80+ corporate sponsors, into the gleeful, continuous production of tech demonstrations, driven by the lab’s other, more ominous motto: “DEMO OR DIE.”

OLPC was launched by Negroponte in 2005 and was effectively shut down in 2014. After traveling the world since at least the early 1980s to sell personal computers to developing nations, Negroponte announced he had created a non-profit organization to produce a $100 laptop “at scale”—in other words, the cost of the laptop could only be this low in the early 2000s if, according to Negroponte, they could amass orders for 7-10 million laptops. Essentially, despite his often repeated statement that OLPC is not a laptop project but rather an education project, its essence was the same as the Hessdorfer Experiment or SEEK: got a poverty problem? Get a computer! Worse yet, don’t do a study of whether what the community or nation needs are—JUST GET A COMPUTER.

Here’s what Negroponte said in a Ted Talk from 2006, suggesting that even if families didn’t use the laptops, they could use them as light sources:

I was recently in a village in Cambodia—in a village that has no electricity, no water, no television, no phone. But it now has broadband internet and these kids, their first word is “Google” and they only know “skype,” not telephony...and they have a broadband connection in a hut with no electricity and their parents love the computers because they’re the brightest light source in the house. This laptop project is not something you have to test. The days of pilot projects are over. When people say well we’d like to do three or four thousand in our country to see how it works, screw you, go to the back of the line and someone else will do it, and then when you figure out this works you can join as well.

Not surprisingly, as with the lack of forethought in the experiment with the poor gerbils, by 2012 studies were coming out clearly indicating that the laptops—whether they were used in Peru, Nepal, or Australia, made no measurable difference in reading and math test scores. In fact, one starts to get the sense that Negroponte’s truly remarkable skill that he began honing in the late 1960s in the Architecture Machine Group is not design, not architecture, and not tech per se, but rather dazzling salesmanship built on a lifetime pitching humanism and futurism via technological marvels. Even Stewart Brand saw this in Negroponte. Quoting Nat Rochester, a senior computer scientist and negotiator for IBM, “[If Nicholas] were an IBM salesman, he’d be a member of the Golden Circle...if you know what good salesmanship is, you can’t miss it when you get to know him.”

The pitch-perfect ending to this strange story is that in 2013, after selling millions of laptops to developing nations around the world, laptops that again made no measurable improvement in anyone’s lives, Negroponte left OLPC and went on to chair the Global Literacy X Prize as part of the XPRIZE Foundation. However, the prize itself no longer seems to exist and there’s no record of him being with the organization just a year later in 2014—it seems he’s finally, quietly living out his salesman years back at MIT where he began.

XPRIZE, however, does exist, and appears to be the ultimate nonprofit based on nothing more than air and yet more humanist slogans:

XPRIZE is an innovation engine. A facilitator of exponential change. A catalyst for the benefit of humanity. We believe in the power of competition. That it’s part of our DNA. Of humanity itself. That tapping into that indomitable spirit of competition brings about breakthroughs and solutions that once seemed unimaginable. Impossible. We believe that you get what you incentivize… Rather than throw money at a problem, we incentivize the solution and challenge the world to solve it… We believe that solutions can come from anyone, anywhere and that some of the greatest minds of our time remain untapped, ready to be engaged by a world that is in desperate need of help. Solutions. Change. And radical breakthroughs for the benefit of humanity. Call us crazy, but we believe.

In many ways, XPRIZE is the ultimate Media Lab project spanning the world, whose board includes every major corporate executive you can think of, not even aiming to produce things anymore but just “incentives.” And in terms of the lab itself, while Negroponte seems to be practically retired and Wiesner passed away a number of years ago, the Media Lab continues to merrily churn out demos and products for consumers and the military under the leadership of Joi Ito, a venture capitalist with no completed degrees, a godson of Timothy Leary and a self-proclaimed activist. MIT couldn’t have found a better successor for the world-class salesman Nicholas Negroponte.

With her colleagues Darren Wershler and Jussi Parikka, Lori Emerson will continue writing on labs and posting interviews on lab directors at whatisamedialab.com.