Revisiting the Future

Revisiting the Future

In diesem Text, der zuerst in across & beyond—Post-digital Practices, Concepts, and Institutions erschien, blickt die zukunftsweisende Cyberfeministin Cornelia Sollfrank zurück auf die verschiedenen Ausprägungen des Cyberfeminismus in den 1990er Jahren. Ihrer Reise in die Vergangenheit liegt eine Reihe von Fragen zugrunde, die zu einem besseren Verständnis der Gegenwart verhelfen. Was waren die Impulse hinter den technofeministischen Umbrüchen der Zeit? Wie wichen die unterschiedlichen Konzepte der Bewegung von einander ab? Kann Cyberfeminismus auch heute eine Rolle spielen? Gibt es technofeministische Ansätze, die auf gegenwärtige Herausforderungen eingehen?

Techno-feminist Inspiration

“I want the readers to find an ‘elsewhere’ from which to envision a different and less hostile order of relationships among people, animals, technologies, and land […] I also want to set new terms for the traffic between what we have come to know historically as nature and culture.”

– Donna Haraway 1

Despite feminist criticisms about the formation of a canon and historical periodization, it is not possible to revisit cyberfeminism without referencing its originary texts. Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, first published in 1985, must be mentioned as a central piece of techno-feminist thinking.2 Although Haraway herself has never used the term cyberfeminism, the cyborg metaphor as well as her critique of techno-science have provided important references for the numerous cyberfeminist experiments to come. Considered to be one of the most influential feminist commentators on techno-science, Haraway inspired not only feminist theory, but equally feminist art and activism. Though referring to Haraway does not deny the existence of a variety of other key approaches on gender and technology issues, her fundamental critique seems to be of value for techno-feminist thinking like no other.

It is Haraway’s achievement to have significantly contributed to the deconstruction of scientific knowledge as historically patriarchal and of science and technology as closely related to capitalism, militarism, colonialism, and racism. As opposed to liberal feminist efforts demanding equal access, she instead points to the possibilities of a wide-ranging reconceptualization of science and technology for emancipatory purposes. Central to her anti-essentialist approach is the critique of “objective knowledge.” Rather than understanding science as disembodied truth, Haraway emphasizes its social property, including its potential to create narratives. In her words: “[t]he detached eye of objective science is an ideological fiction, and a powerful one."3 As Judy Wajcman puts it: “For Haraway, science is culture in an unprecedented sense. Her central concern is to expose the ‘god trick,’ the dominant view of science as a rational, universal, objective, non-tropic system of knowledge."4 With that comes the challenging of dichotomous categories such as science/ideology, nature/culture, mind/body, reason/emotion, objectivity/subjectivity, human/machine, and physical/metaphysical on the basis of their inherently hierarchical functions. What is particularly relevant to techno-feminist thinking in this work is that it reveals the construction of the “natural” as a cultural practice.

Haraway’s analysis does not lead to an anti-science stance, but rather demands a more comprehensive, stronger, and truer science that includes multiple standpoints. Her concept of “situated knowledge” is a “feminist epistemology that acknowledges its own contingent and located foundations just as it recognizes the contingent and located foundations of other forms of knowledge.”5 With her concept of the cyborg, Haraway goes a step further and offers a concrete conceptual tool for rethinking feminist-socialist politics in the age of techno-science. The term “cyborg” stands for cybernetic organism, an entity that is neither natural nor mechanical, neither individual nor collective, neither male nor female—an integrated human-machine-system. The cyborg is more than the sum of her parts, and thus, as Karin Harrasser noted, enables new forms of social and political practice by suggesting the artificiality of corporeality while exposing the collective nature of subjectivity as well as the inherent politics of inter-connectivity.6 Haraway’s cyborg figure symbolizes a non-holistic, non-universalizing vision for feminist strategies and facilitated, amongst other things, an early rethinking of subjectivity under networked conditions.

Instead of resorting to a technophobic utopian model embraced by a number of twentieth-century feminist activist groups in the context of eco-feminism and radical feminism, Haraway argued for the channeling of an inborn agency towards the reinvention of feminist and socialist politics within the paradigms of networking, informatization, miniaturization, and the entanglement of bio- and information politics. The cyborg’s subversive potential, however, remained largely unexplored; it seems to have fueled age-old male fantasies of the perfect and controllable female body rather than allowing for non-essentialist subjectivities to emerge.

Early Cyberfeminism

Depending on the source, the term cyberfeminism was first used around 1991 by both the English cultural theoretician Sadie Plant and the Australian artist group VNS Matrix, independently from each other. Subsequently, the term was applied in many different, even contradictory ways, which is why it is difficult to assign a coherent theory to it. Nevertheless, it is useful to start with a critical exploration of its early meaning, because in recent historicizations and revivals of cyberfeminism it is usually these early versions that are referred to.

Although applying very different means—cultural theory and art practice—both Plant and VNS Matrix pursued the same objective: throwing overboard the traditionally technophobic versions of earlier feminisms by propagating an intimate relationship between women and technology. Finally, technology was conceived as sexy for women.

Planting Optimism

In her 1997 book, Zeroes and Ones, Plant brings together the past, present, and future of technological developments and interweaves them with suggestive quotes and excerpts from feminist theory and literature, psychoanalysis, philosophy, and cyberpunk material. The methodological medley resembles an essay rather than a scientific work and takes the reader on a learned tour through disciplines and centuries with the sole purpose of collecting evidence for what Plant makes us believe. Not only, she wrote, had a “genderquake” taken place in the 1990s, but also

“[w]estern cultures were suddenly struck by an extraordinary sense of volatility in all matters sexual: differences, relations, identities, definitions, roles, attributes, means, and ends. All the old expectations, stereotypes, senses of identity and security faced challenges."7 She attributed these massive upheavals, to a large degree, to technological development.

Beyond that, and contrary to popular belief, women significantly contributed to this development, according to Plant. The chain of evidence obviously includes programming pioneers Ada Lovelace and Grace Murray Hopper, but also extends to anonymous spinners and weavers, amazons, witches, goddesses, robots, cyborgs, mutants, and chat bots. Towards this alternate history Plant seeks empowerment in the number zero, which she writes should no longer represent the unthinkable nothingness (of the female) as opposed to the unity of the (male) one. “There is a decided shift in the woman-machine relationship, because there is a shift in the nature of machines. Zeros now have a place, and they displace the phallic order of ones,” as Wajcman paraphrases Plant.8 Most importantly, however, it is the decentralized and horizontal structure of the internet itself to which Plant ascribes transformative powers—transitioning us from a male to a female era. “The growth of the Net has been continuous with the way it works. No central hub or command structure has constructed it, and its emergence has rather been that of a parasite, than an organizing host."9 According to this view, new technologies not only subvert the male identity; even more exciting is the possibility of inventing endless new identities, thus undermining binary heteronormative subjectivities.

And this is what has survived as the memory of what cyberfeminism was: an excessive belief in the powers of new technologies to transform gender relations due to their inherent properties. Following Wajcman’s criticism, what Plant largely ignores are the social and political realities of new technologies. Therefore, in my reading, as in Wacjman’s, it is not exaggerated to accuse Plant’s version of cyberfeminism of a certain “technological determinism.” If the desired change comes automatically with the advent of new technology—at the click of a mouse, so to speak—there is no space and no need for active political engagement. Such celebration of technology must, therefore, be suspected of political conservatism rather than any form of emancipation. Wajcman goes a step further and reveals another problematic aspect in Plant’s writing: the inconsistency in the way she uses gender categories. While conceptualizing woman’s fragmented and liquefied identities, Plant celebrates “universal” feminine attributes. This leads Wajcman to call her utopian version of the relationship between gender and technology “perversely post-feminist”:

“It is a version of radical or cultural feminism dressed up as cyberfeminism and is similarly essentialist. The belief in some inner essence of womanhood as an ahistorical category lies at the very heart of traditional and conservative conceptions of womanhood. What is curious is that Plant holds on to this fixed, unitary version of what it is to be female, while at the same time, arguing that the self is decentred and dispersed."10

It is important to revisit Plant’s writing almost two decades later. Despite the shortcomings of her theory, her achievement was to enthuse a large crowd. She had her finger on the pulse of the time and used the premonition of something big to come not only to bring up gender issues, but to ascribe an essential and empowered role to women throughout history. After women having been excluded from technology equally by patriarchal society and feminism for too long, the time was ripe to paint an optimistic picture of female involvement. The promise of freedom and pleasure deriving from an intimate relationship between women and technology was hard to resist. Sobering political analysis that would include in-depth research on how gender, technology, and power are intrinsically sealed together, as well as inevitable fights over political strategies, could wait for later.

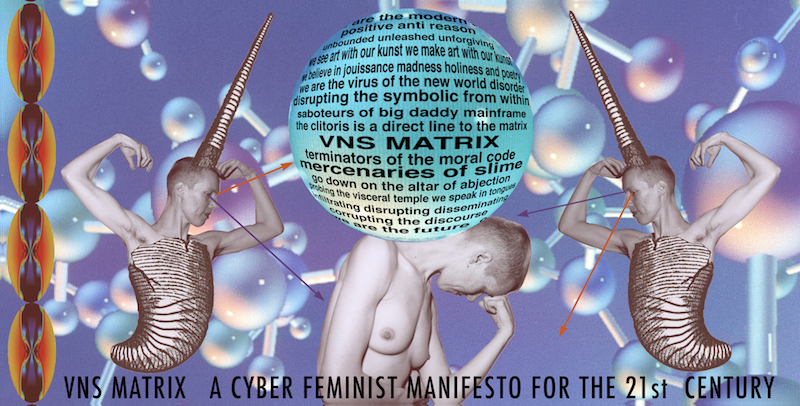

VNS Matrix—The Future Cunt

The Australian artist group VNS Matrix, consisting of Virginia Barratt, Julianne Pierce, Francesca da Rimini, and Josephine Starrs, can claim to have been the first to add feminist fuel to the flaming embers of digital networked technology. Their 1991 Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century is a wild and poetic expression of their desire to contaminate sterile technology with blood, slime, cunts, and madness and to repurpose technology for anarchic feminist aims.11

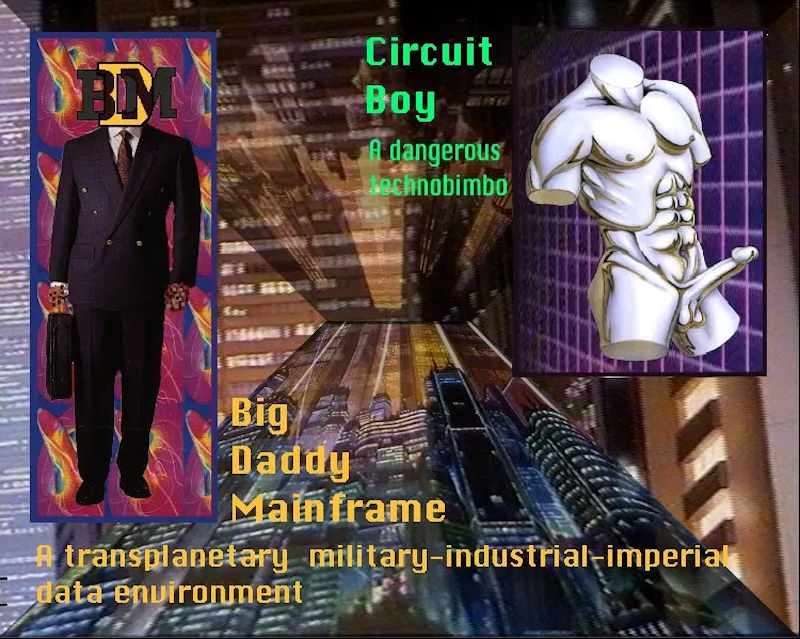

Tellingly, the manifesto was circulated on billboards—rather than electronic networks—but nevertheless became viral. So did their next project in 1995: the computer game All New Gen. The game, which existed only as a prototype and could only be viewed in gallery spaces, nonetheless disrupted stereotyped thinking about gender and technology. The heroines of the game, “cybersluts” and other “anarcho cyber-terrorists,” infiltrated the ruling order of phallic power represented by “Big Daddy Mainframe” to disseminate seeds of chaos and confusion and eventually bring down the system. Again, the significance of the intervention did not lie in its advanced use of technology, but rather in its symbolic force, in its powerful poetic language. The imaginary space of electronic networks did have the potential “to stretch imagination and language to the limit; it is a vast library of information, a gossip session, and a politically charged emotional landscape. In short, a perfect place for feminists,” as Beryl Fletcher put it.12

A lot of what VNS Matrix originated is echoed and extended in Sadie Plant’s writings. What they have in common is their speculative techno-determinism that assumes a special connection between the basic features of digital networked technologies and “the female”—that “the new technology cannot be brought back under the old order,” as Wajcman has interpreted this attitude.13 However problematic we may find this approach today in terms of feminist politics, these early cyberfeminists had an empowering effect in historical context. In recent years, we could even witness a kind of nostalgic revival of cyberfeminism for which VNS Matrix’s ironic visuals and tongue-in-cheek literary outpourings have been particularly attractive. It is important, however, to understand early cyberfeminism as a child of its time. In an online world rife with discriminatory and sexist assaults, as we have it today, fantasies about overcoming the flesh, about overcoming embodied experience by simply dissolving gendered bodies into the realm of their digital representations, seem to miss the point.

Cyberfeminist Networking

Numerous theories have been elaborated, and activists and artists have contributed to the diverse field of cyberfeminism that gained great popularity in the mid- and late-1990s. These are elaborated below.

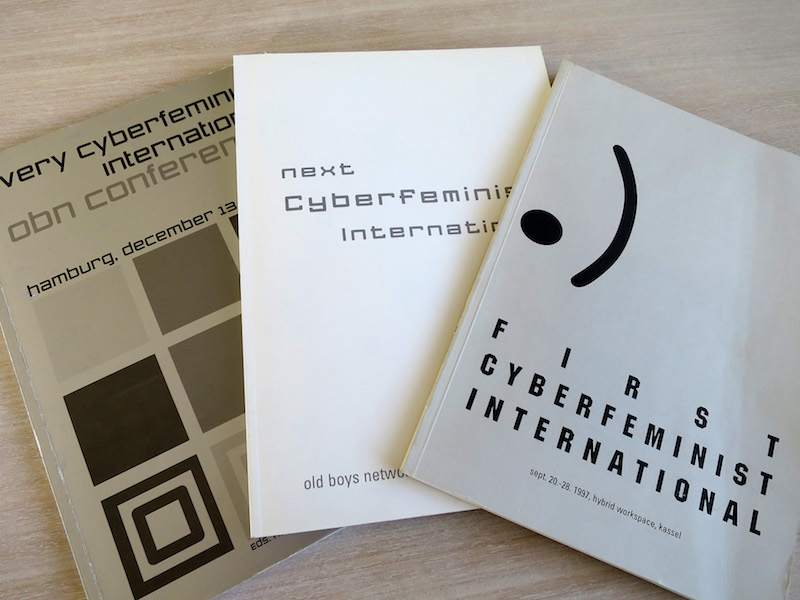

Old Boys Network

A special occasion to solidify the discourse and build an actual network came along in 1997 when the curators of the Hybrid Workspace at documenta X in Kassel offered me the opportunity to put together one of the ten-day program blocks on the topic of feminism and technology.14 My idea was to use this mega-event as a platform not only for promoting cyberfeminism but also for launching the first international cyberfeminist alliance: the Old Boys Network (OBN).15 The first working group I initiated led to the foundation of the network in summer 1997 in Berlin. The founding members were artist historian Susanne Ackers, artist Ellen Nonnenmacher, journalist Vali Djordjevic, artist Julianne Pierce, and me. Throughout the five years to follow, OBN constantly changed its shape and internal form. Varying constellations of members managed to actively involve about 180 people altogether, at different levels of involvement.16

As our starting point we used the idea of appropriating the term cyberfeminism from its inventors and expanded it to also include aspects beyond identity politics and representation, such as the material and sociological aspects of new digital technologies. Everyone who declared herself a “woman” was invited to contribute. Resetting the meaning of the term cyberfeminism, on the one hand, built on the attention early cyberfeminism had generated, while, on the other hand, opened it up to other, less essentialist interpretations. Thus, cyberfeminism could function as an open projection field in this new context, with the capacity of reflecting manifold individual fantasies, desires, and concepts. OBN turned cyberfeminism into a pluralistic concept inspired by postmodern (feminist) thinking, which put an emphasis on difference rather than unity. As was expressed in OBN’s mission statement: “With regard to its contents—the elaborations of “cyberfeminisms”—our aim is the principle of disagreement!"17 In the words of Claudia Reiche, an old boy who joined in during the first Cyberfeminist International: “Operating according to the principle of dissent means that there are no representative statements, no common messages, no coherent forms of expression. The focus is on the differences, the contradictions, the disagreements. And it is through the perception of the thus emerging holes that the stitches of the network become visible—rather than through a laced-up strap.” This structure would require us “to conceive a variety of cyberfeminist techniques to be exemplified and assessed in specific approaches."18

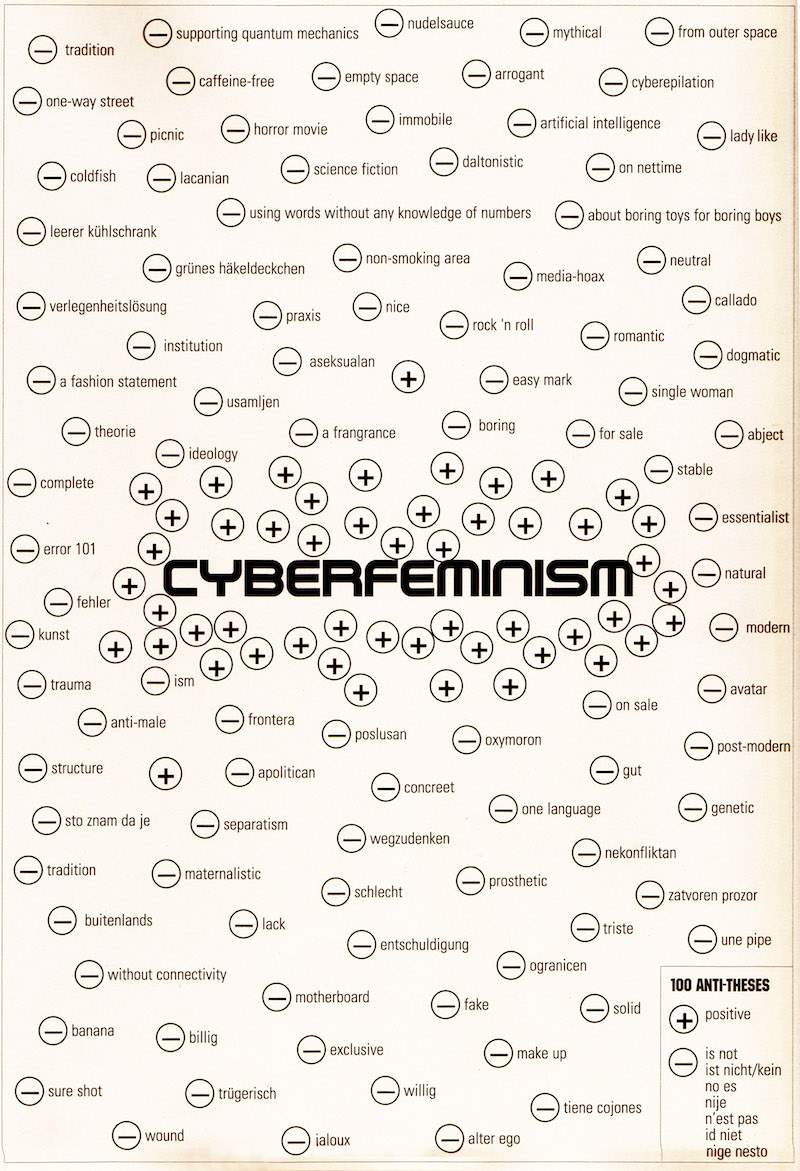

In most attempts to write the history of cyberfeminism as well as the recent nostalgia about it, the role of OBN as an organization whose aim was to radically reinvent cyberfeminism by celebrating diversity and multiplicity has been largely overlooked or misunderstood. Instead of providing a definition and a clear, set political agenda, we asked a question: what is cyberfeminism? Under the motto “Targeting Content: Cyberfeminism,” we published an open call and asked for suggestions regarding an expanded approach to cyberfeminism. There were no provisions in terms of format or contents, and we were able to invite thirty participants to join us for the first Cyberfeminist International. The contributions ranged from spatial design, dinner parties, radio shows, artworks, interventions, a dance party, and performances to poetry, philosophy, media theory, and art history. Hosted by one of the most prominent exhibitions for contemporary art, a new generation of cyberfeminists was born in a kind of semi-curated and self-organized mode.

In the euphoric atmosphere of the conference, everyone was able to make a contribution, and, despite the enormous diversity, no confrontations or fights occurred. Instead, the multiplicity that came into the picture was celebrated in a joint manifesto, The 100 Anti-Theses, of what cyberfeminism was not.19 This performative rejection of the political need to define our commonalities indicated a new beginning that later has often been misread as lack of political rigor. In fact, it marked a departure, a new era of the discourse on gender and technology, spanning generations, languages, disciplines, cultures, and even incompatible political affiliations.

This could be one possible narrative of the history of OBN: the first Cyberfeminist International as a prelude to the networking activities to come. In the five years of OBN’s activities two more international conferences were held, and the conference proceedings with all individual contributions were published online and in print.20 In addition, OBN made contributions to numerous international festivals, conferences, exhibitions, and publications in the fields of media and performance art, media activism, feminist science, and feminist art criticism. One might assume, therefore, that OBN was mainly a real-life network, and digital networking was merely something that was theorized about. But OBN also experimented with the possibilities the internet offered at the time. Our hybrid self-organized structure—consisting of a self-declared (changing) core-group and various project groups embedded in a larger network—was organized through its own mailing list, IRC chats, a website, and temporarily even a server of its own, experimenting with new publishing formats as well as live interaction.

Networking—The Mode is the Message

The name Old Boys Network clearly indicated the form of our organization: the network. Our slogan, “The Mode is the Message—the Code is the Collective,” suggested an emphasis on process and an awareness of how things were done. In the 1990s, the term “network” resonated with non-hierarchical communication, with distributed relationships that mysteriously interwove to create a tear-proof texture, nevertheless fluid and dynamic, and, if nothing else, with the ability to challenge and undermine rigid and hierarchical power structures. At the same time, it remained a form that was elusive and susceptible to obfuscation, which, in combination with political concerns, could feed suspicions.

Certain formal aspects of our organization, however, were clearly defined and subjected to defined rules. For all public appearances, for example, we had agreed that at least three Old Boys would have to present the network and perform the principles of difference and disagreement by providing three different angles on the same topic. Other aspects of our organization, in particular those regarding the internal structures and the modes of decision-making, remained implicit. It is my contention that the vagueness regarding who and what OBN actually was and how it functioned reinforced a certain opaqueness that eventually added to its popularity.

If and how the Old Boys Network has eventually expanded and exceeded earlier theories and practices of cyberfeminism, however, still requires an in-depth investigation. With our refusal to work on a single general definition of cyberfeminism came the proliferation of many individual approaches, some referring to earlier theories, others writing new theories or inventing new forms of theory and practice. The scope of the contributions was wide and included, for instance, the inescapable identity and body politics as well as issues of representation in cyberspace, but also feminist history, the setting-up of safe spaces such as mailing lists, dinner parties, workshops, digital civil rights, privacy, and security issues, free software, immaterial labor, working conditions in the hardware sector, the implications of the military medical complex, hacking as methodology, artistic espionage, artistic uses and abuses of data such as DJing, remixing, and sampling, conflicts over intellectual property, and the realpolitik of gender equality policies in IT industry and games culture. Last but not least, it included the creation of the cyberfeminist network itself.

Working with the Old Boys Network was an overwhelming experience. There was an atmosphere of departure, and we were right in the middle of it. What digital network technologies would bring to the world, how they would change our daily lives, how they would expand our access to information and communication while, at the same time, become the means of unforeseen control and exploitation was pure speculation at the time. It certainly was exciting to get involved at such an early state.

Being in the World with Others

By creating spaces and situations in which diverse approaches could be connected and discussed, OBN provided the stage and the framing context using the proclaimed ambiguity of the term cyberfeminism as a starting point for experimentation. Along these lines, our network could simply be understood as a form of organization, a form of getting organized, or a way to self-organize within or in parallel to traditionally hierarchical systems of academia and the art world. Verena Kuni pointed to this aspect, discussing the emerging opportunities that new technologies offer for “feminist networking” in a male-dominated art world.21 Her deliberations are largely geared towards career opportunities in this context—something that should become one of the central aspects of all gender and technology activities in the context of liberal feminism. The name Old Boys Network actually invites such an understanding. Referring to the informal system of mutual support—typical within male white elites—it parodies this influential form of invisible power structures without necessarily excluding the aim for a similar form of mutual support. I do not want to deny the relevance of such an approach, although, in my understanding, much more was at stake.

Manuel Castells has suggested the term “networked individualism” for an evolving social pattern that allowed individuals to form “virtual communities, online and offline,” on the basis of their interests, values, affinities, and projects.22 What this term tries to grasp is more than just a way of getting organized. It is about dissolving the old dichotomy between the individual and the collective/community in order to bring about more than just a collection of isolated individuals: a new form of being in the world with others. An essential feature for this cultural shift to happen is, according to Castells, the technological infrastructure on which it is based: the internet. Although, like the techno-determinist claims of Plant and others, Castells’ new forms of sociability are directly derived from what is described as an essentially positive technological development, they have opened up a new space for thinking about collective agency.

With his different notion of the “networked individual,” Kristóf Nyíri even goes a step further and speaks of a new type of personality emerging in networks: “[t]he network individual is the person reintegrated, after centuries of relative isolation induced by the printing press, into the collective thinking of society— the individual whose mind is manifestly mediated, once again, by the minds of those forming his/her smaller or larger community” (online).23 In contrast to the concepts of networked individualism as elaborated by Castells and others, networking in Nyíri’s sense means far more than spawning new forms of sociability; it deeply affects concepts of subjectivity and thus collective agency.

It is not surprising that networks as a site and networking as an activity became popular with feminists. The promises contained in these paradigms met the feminist criticism of the male individual as the origin of subjectivity. It was part of the excitement in and around OBN that we had the opportunity to experiment with such emerging forms—not just in and through our individual expressions, but also in the way we were connected. Haraway’s cyborg had provided the inspiration for this new condition of being in the world as interconnected subjectivities. This is probably the reason why it is so difficult to understand OBN from a present-day perspective. The website is an archive that contains documentation of a lot of our activities, but it can hardly communicate this spirit of being networked. Trying to explore the nature of OBN and assessing its political impact would require thorough social science research that involves more than reading the texts and looking at the pictures published on the website—and more than just one perspective. In any case, the time OBN was operative was a period of collective feminist agency for which we provided the underlying structure.

Together with many other groups and initiatives, OBN belonged to the context of 1990s net culture. In small niches for which the critical confrontation with then-new technologies was characteristic, ideas such as Netzkritik (net criticism), tactical media, net art, and hacktivism were contrived and tested, and together formed a disparate yet networked environment that in no small part was inspired by hacker culture.24

Next Stop after Utopia

In the decade after the end of OBN, the notion of “digital culture” as a subculture and domain of experts has shifted to become the general societal condition. Not only do digitally networked media influence essentially all areas of life, the operational logic of networked communication inscribes itself continually and ever more deeply into all aspects of social organization and human experience, which gives rise to endless social science and cultural theory research. What had an ultimately shocking effect within these larger social upheavals were the revelations of Edward Snowden in 2013. Deleuze’s notion of the “control society,” which has haunted net culture since the early days, eventually pressed its way to the fore, as was made apparent by Snowden.25 It has become hard to deny that the very technology that was reason to dream of new forms of political empowerment has turned out to be the means of comprehensive corporate and governmental surveillance and control—for everybody. The network and the networked individual, once the embodiments of new forms of resistance, now have become the basis for new forms of exploitation and oppression.

It was Rosie Braidotti who, as early as 1996, spoiled the party when she wrote that the large scale of the digitization of society would mainly lead to an increasing “gender gap”: “All the talk of a brand new telematic world masks the ever-increasing polarisation of resources and means, in which women are the main losers. There is strong indication therefore, that the shifting of conventional boundaries between the sexes and the proliferation of all kinds of differences through the new technologies will not be nearly as liberating as the cyber-artists and internet addicts would want us to believe.”26 Braidotti’s theory was not dismissive of cyberfeminism in general; she rather included materialist and socio-economic aspects and, therefore, has arrived closer to contemporary reality with her speculation.

A reality check of gender and technology today does not give any reason for optimism. As various overviews and studies have shown, non-whites/non-males/non-heterosexuals are still largely excluded from the creation of the very technology that shapes us and our ways of interacting with the world.27 And self-proclaimed technical undergrounds such as FLOSS (Free Libre Open Source Software), the hacker scene, or hacktivist cultures provide an even more shocking scenario.28

Having arrived in the twenty-first century, one has to ask what has happened to cyberfeminism and other techno-feminist aspirations. It is needless to say that in the light of recent developments, they appear naïve at best. The phallic power of Big Daddy Mainframe not only rules supreme, it is ever expanding. It is my contention that, in order to deal with current challenges from a feminist perspective, it is indispensable to revisit and critically assess 1990s cyberfeminisms in their complexity. We need to understand which aspects were specific to the times they were conceived, and which aspects still have the potential to provide valid references for contemporary thinking. More than ever, there is the need for techno-feminist theory and practice, and it has to learn from the past instead of just indulging in nostalgia—or defying it.29

New Dimensions

As Wajcman and other techno-feminist theoreticians have pointed out, technology is a social construction—a culture—in itself and therefore can become subject to transformation.30 Technology may be a system that generates power—thus reinforcing hierarchical categories such as gender, race and class—but not in a determinist way. “Instead of treating artefacts as something neutral or value-free, social relations are materialized in tools and techniques,” which allows for the reverse. Only more inclusive and diverse techno cultures hold the potential for the transformation of technology.31 This shift in perspective allows for the social dynamics around technology to change and has offered a new space for interventions.

Critical and gender-aware techno-cultures take this as a starting point: the creation of diversity by taking into account the social realities of non-whites/non-males/non-heterosexuals in the use and development of technology. As elaborated elsewhere, intersectional techno-feminist activities exist, but the field is widely spread.32 Understanding technology as a gendering as well as gendered space asks for destabilizing conventional gender differences through questioning and reshaping technology itself. This is what also has been called a “(re)politization of the use, design and development of technology for feminist and social justice purposes” by the organizers of the TransHackFeminist Event in 2014 in Spain.33 This loose context that is organized through different mailing lists promotes and practices various tactics and strategies, ranging from queer-trans-feminist hacker spaces to hackathons and crypto parties, and has also collectively authored an extremely comprehensive manual that brings together the expertise of a diverse community of activists from around the world.34 The authors provide detailed technical knowledge, but also stress the importance of political consciousness raising, collective action, and solidarity. Core strategies that are discussed and applied are the formulation and implementation of codes of conduct for mixed environments, and the establishment of safe spaces.35 The manual furthermore includes various privacy and security issues with aspects such as assessing one’s digital traces, creating and managing multiple online identities, assuring anonymous connections and online communication, creating tools and platforms for collaboration, safe handling of data, and advice on how to deal with trolls, all in order to regain control, at least to a certain degree, over the technologies we use on a daily basis. Without a doubt, the practices described in the manual are the essentials of technical empowerment, but it also becomes clear that the problems—of gender inequality as well as surveillance and control—cannot be solved through technical measures alone. Just as gender equality cannot be forged at the click of the mouse, as some early techno-feminists envisioned, the use of crypto-tools will not be the solution to secure mass communication. Firstly, the business models of mass communication depend to a large degree on collecting private data and will remain so, and secondly, the use of encryption still requires expert knowledge that is not easily available for all.36 While the manual is a great example of techno-feminist knowledge sharing, the techniques included hardly go beyond the notion of digital self-defense; it includes some strategies for fighting back, but it lacks utopian ideas.

Unlike in the 1990s, when cyberfeminism provided a strong reference term for the diverse techno-feminist approaches of the time, the field today is more fragmented and confusing. The above mentioned TransHackFeminist context, for example, is a largely activist context, active also in the global South. There are few connections from this activist community to the art world or to cultural/political theorists, which is why their rather ambitious and differentiated concerns are not communicated to a larger audience. Although theoretically inclusive, the field appears to be confined to a subculture.

The cyberfeminist succession in the art world is mainly concerned with the representational surfaces of the WWW, social media, and games culture and avoids tackling the complexities of gender and technology politics—not to speak of a critical confrontation with the extremely hierarchical and patriarchal art world. And while the notion of post-gender once was a promising attraction, the signs point that old gender stereotypes are being reinforced.37 The cyborg fever is over and with it the dreams of transcending the body to become posthuman. What once provoked liberating fantasies about the relationship of technology and subjective sensitivities, about autonomy and heteronomy, has degenerated into a symbol for the assimilation of former counter-cultures by the unholy alliance of capital and techno-science. The state of being “networked” has lost its fascination for the “dividual individuals” of the control society, who instead busy themselves inventing escape strategies.38

The question arises as to what level a new techno-feminist agenda can be conceived that takes into account radical, queer, trans, feminist, and techno activisms, as one example of specific agency, while at the same time making use of the resources and capacities offered by theory and art practice. The Xenofeminist group Laboria Cuboniks, a collective that emerged in 2014, asks exactly for such an emancipatory politics that would connect localized politics of immediacy to a kind of scalable theory able to confront abstract global systems of injustice: “[t]ransiting between such scales—between the concrete here and now, and the untouchable, yet thinkable abstract—is a requirement for 21st century emancipatory politics, involving an expanded conception of ‘specificity’, ‘particularity’ and ‘situatedness.’"39 So far, however, Xenofeminism remains “the call for” such a novel theory.

This takes me back to the introductory statement by Donna Haraway quoted at the start of this text, in which she invites her readers to “find an elsewhere,” an imagined future from which we can rethink the present. What do we see in our present that we do not like, that we cannot live with, that needs to change? What would it look like in an ideal future society/world? This move to utopian thinking brings us close to fiction and science fiction, a genre that has long been popular with feminists for good reason. Rethinking gender relations is certainly the most important aspect of feminist science fiction, but I believe that contemporary techno-feminist utopias have to open up and include a rethinking of technology in terms of its dependency on capitalist logic. Questioning gender and technology paradigms cannot take place without seriously questioning capitalist principles of growth and exploitation. This is where techno-feminism has to meet other social movements. Utopia will be there as long as we are searching for it—together. Let’s chase away the libertarian ghosts of Silicon Valley who don’t know anything but greed and competition.

What are “our” images of desire? What are “our” codes for hope? Why not reactivating the cyberfeminist expertise on the future? Only by drafting our visions can we go beyond the contradictions produced within society and get closer to what neither theory nor practice have realized yet. The most important tool for forming an opposition to existing structures will not be the use of advanced crypto-technology, but rather the use of imagination.

You can buy a print copy of across & beyond here.

- 1. Donna Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” Socialist Review, no. 80 (1985).

- 2. Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs.” In this essay I use the term “techno-feminism” as an umbrella term for a variety of feminist politics that address—in theory and practice—the coded relationship between gender and technology, and aim at changing this code by opening up the potential of technology to support emancipatory purposes.

- 3. Donna Haraway, Primate Visions: Gender, Race and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989), 13.

- 4. Judy Wajcman, TechnoFeminism (Oxford: Polity, 2004), 83.

- 5. Ibid., 86.

- 6. Karin Harrasser, “Herkünfte und Milieus der Cyborg,” in Die Untoten—Life Sciences & Pulp Fiction (Hamburg: Kampnagel, 2011).

- 7. Sadie Plant, Zeros and Ones (London: Fourth Estate Limited, 1997), 37.

- 8. Wajcman, Technofeminism, 64.

- 9. Plant, Zeroes and Ones, 49.

- 10. Wajcman, Technofeminism, 73.

- 11. VNS Matrix, Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, www.sterneck.net/cyber/vns-matrix/index.php. First version published in 1991 as image on billboard.

- 12. Beryl Fletcher, “Cyberfiction: A Fictional Journey into Cyberspace—or How I became a Cyberfeminist,” in CyberFeminism: Connectivity, Critique+Creativity, eds. Susan Hawthorne and Renate Klein, (North Melbourne: Spinifex Press, 1999), 351.

- 13. Wajcman, Technofeminism, 65.

- 14. Hybrid Workspace, https://monoskop.org/Hybrid_Workspace (accessed April 26, 2016).

- 15. The website of OBN is available under www.obn.org and now functions as an archive for most of the material produced by OBN.

- 16. The text “The Art of Getting Organized” (2013) is a detailed account and analysis of the personnel and structural development of OBN. German only: http://artwarez.org/195.0.html (accessed July 29, 2016).

- 17. Old Boys Network, “Frequently Asked Questions,” http://obn.org/inhalt_index.html(accessed November 11, 2015).

- 18. Claudia Reiche, Cyberfeminismus, was soll das heißen? (Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Geschlechterstudien, 2002), 47. Translation from the German by the author.

- 19. Old Boys Network, The 100 Anti-Theses, http://www.obn.org/cfundef/100antitheses.html (accessed July 29, 2016).

- 20. Old Boys Network, OBN Projects, http://obn.org/inhalt_index.html (accessed August 23, 2016).

- 21. Verena Kuni, “Ganz automatisch ein Genie? Cyberfeministische Vernetzung und die schöne Kunst, Karriere zu machen,” in Musen, Mythen, Markt, Jahrbuch VIII, ed. Sigrid Haase (Berlin: Hochschule der Künste Berlin, 2000), 41–50.

- 22. Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996).

- 23. Kristóf Nyíri, “The Networked Mind,” in Studies in East European Thought, vol. 60, no. 1/2 (New York: Springer, 2005), 149–158.

- 24. Although it was part of the critical net cultures’ self-understanding to deconstruct technology on the basis of their social and political implications, it was reserved for the “experts” to address gender-related issues. The role of cyberfeminism and other techno-feminisms within these subcultures is another issue worth exploring and would make a text in itself.

- 25. Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” in October, vol.59 (New York, 1992).

- 26. Rosi Braidotti, “Cyberfeminism with a Difference,” in New Formations, no. 29 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1996).

- 27. Statistical overviews can be found in: Lindsey Gilpin, “The state of women in technology: 15 data points you should know,” TechRepublic, 2014, http://www.techrepublic.com/article/the-state-of-women-in-technology-15-...(accessed September 19, 2016); Emily Peck, “The Stats On Women In Tech Are Actually Getting Worse,” the Huffington Post, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/27/women-in-tech_n_6955940.html (accessed September 19, 2016).

- 28. Exact figures are not available for the hacker and hacktivist scene for obvious reasons. In free software development recent overviews show different figures ranging from two percent to eleven percent females in the workforce. See also the Floss survey 2013, http://floss2013.libresoft.es/results.en.html (accessed April 27, 2016).

- 29. Examples of recent, rather uncritical reviews of cyberfeminism can be found in: Sonja Peteranderl, “Die Pionierinnen des Cyberfeminismus sagen den Tech-Cowboys den Kampf an,” Wired Germany, June 2, 2015, https://www.wired.de/collection/life/das-cyberfeminismus-kollektiv-vns-m... Claire L. Evans, “We are the Future Cunt: Cyberfeminism in the 90s,” Motherboard, 2014, http://motherboard.vice.com/read/we-are-the-future-cunt-cyberfeminism-in-the-90s(accessed September 19, 2016). Others improperly reduce cyberfeminism in an attempt to deny its relevance altogether, such as in Armen Avanessian, dea ex machina (Berlin: merve, 2015).

- 30. Judy Wajcman, “Feminist theories of technology,” in Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 34, (2010): 143-52.

- 31. Ibid., 147.

- 32. Cornelia Sollfrank, “Gender and Technology Trouble,” in Tactical Media Anthology, eds. David Garcia and Eric Kluitenberg (Cambridge: The MIT Press, forthcoming 2016).

- 33. Website of the ongoing project: https://transhackfeminist.noblogs.org/ (accessed August 23, 2016).

- 34. The manual is available in English and Spanish and has been produced and published through Tactical Tech Collective, Berlin, 2015.

- 35. The concept of “safe space” is elaborated in the GeekFeminismWiki, http://geekfeminism.wikia.com/wiki/Safe_space (accessed August 23, 2016).

- 36. Dmytri Kleiner elaborates on these interrelations in “Hackers can’t solve Surveillance,” http://www.dmytri.info/hackers-cant-solve-surveillance/ (accessed August 24, 2016).

- 37. A good example seems to be the new desire for authenticity as acted out, for instance, by the girls “crying on camera,” as written about in: Sara Burke, “Crying on Camera: ‘fourth-wave feminism’ and the threat of commodification,” UX: Art+Tech, SFMoMA, May 17, 2016, http://openspace.sfmoma.org/2016/05/crying-on-camera-fourth-wave-feminis....

- 38. Deleuze, “Postscript,” 5.

- 39. Laboria Cuboniks, Xenofeminism—A Politics for Alienation, 2014, http://www.laboriacuboniks.net/ (accessed August 23, 2016).